The History of the Finds: Nefertiti and the Pergamon Altar

News from 01/13/2023

Renowned the world over, they are the absolute highlights of the Museum Island: the bust of Nefertiti and the reconstructed Pergamon Altar. Both came to Berlin by legitimate means.

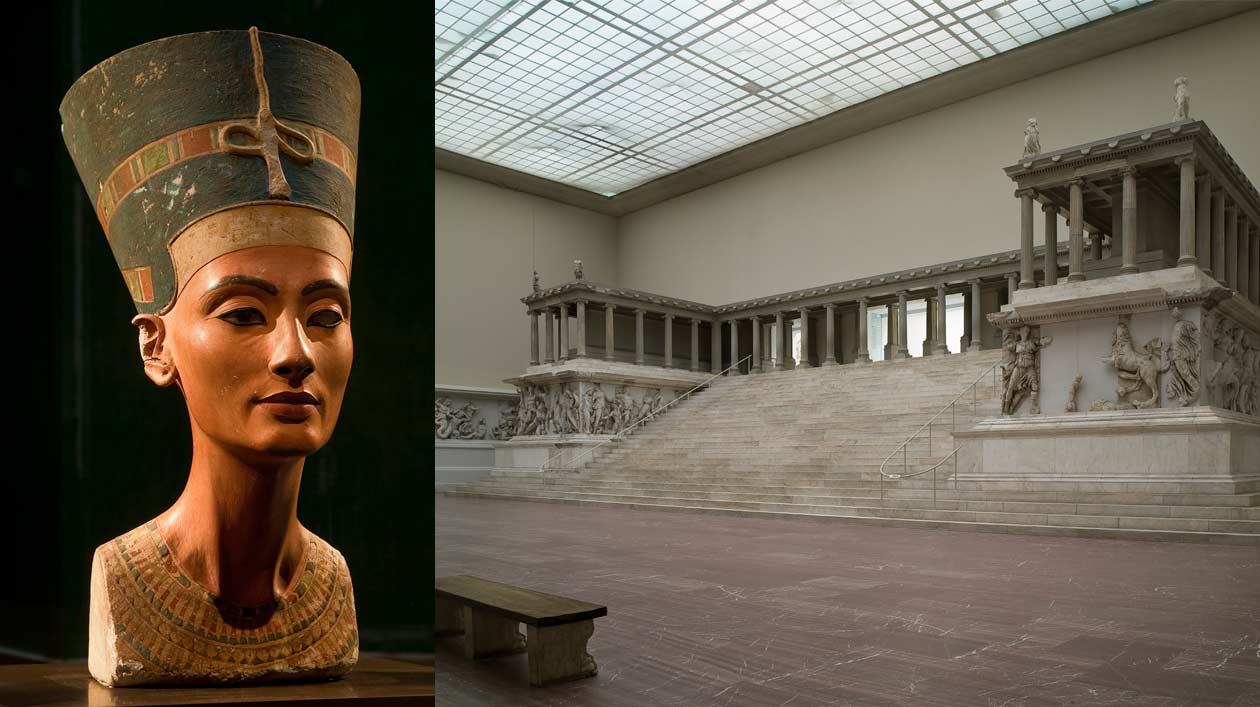

Nefertiti

The bust of Nefertiti was discovered in Tell-el-Amarna in 1912 during a research excavation project authorized by the Egyptian government. The project, undertaken by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society), was funded by James Simon, a Berlin entrepreneur and esteemed patron of the arts, and led by Professor Dr. Borchardt of the Kaiserlich Deutsches Institut für Ägyptische Altertumskunde (Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Antiquities).

From the beginning, the agreement with the Egyptian side provided for the (then customary) equal division of all finds in exchange for the excavation’s funding. To ensure that both parties received equal shares of what was uncovered during the excavation, it was agreed in advance that the archaeological team would divide the find into equal lots with all objects listed in detail. The Egyptian antiquities service, representing the Egyptian government, selected its half; the other half went to Berlin. Photographs of the outstanding finds were available – including one of the bust of Nefertiti – and they clearly portrayed the beauty and quality of the objects. In addition, the opened boxes were presented for examination of the objects. There can therefore be no question of deception during the partage, or division of the objects. The documents clearly prove that Nefertiti was legitimately awarded to the Berlin party in the course of the division of the finds.

The objects of the Amarna partage passed lawfully into the possession of the sole financial sponsor of the excavation, James Simon. Initially, Simon kept the Nefertiti bust in his villa in Tiergartenstrasse. In 1920, he donated the bust, along with the other excavation finds, to the museums of Berlin. Today the Nefertiti bust is exhibited as part of the Egyptian collection in the Neues Museum on Museum Island.

Pergamon Altar

In the 1860s, Carl Humann, who was working as a road-building engineer in the region, became aware of the ruins of the ancient city of Pergamon in the northwest of present-day Turkey. Inspecting the site, he found that marble fragments were being burned in lime kilns by the local population. The Pergamon Altar had already been dismantled in early Byzantine times (7th/8th century), and the slabs of its two relief friezes had been repurposed as spolia in a fortification wall. Humann sent some of these reliefs to Berlin, where they were recognized as parts of the Pergamon Altar, at the time known only from written sources. His intervention had saved the fragments from the lime burners. It was only in the course of the later excavation begun in 1878 that he recovered the foundation of the altar, which remained on the acropolis of Pergamon.

In Berlin, the relief slabs and the few surviving architectural remnants were reassembled for the first time into an altar and the monument made accessible to visitors – initially in the first, provisional Pergamonmuseum from 1901 to 1907, then later in the actual Pergamonmuseum on Museum Island, which was opened in 1930 and continues to house the altar today. Incidentally, modern supplements make up well over 80% of the world-famous reconstructed western facade of the altar, with its grand staircase and porticoes: only a few architectural parts (fewer than half a dozen columns with capitals, cornices, steps) and the two relief friezes are original; the rest consists of reconstructed elements made of Portuguese marble, artificial stone and plaster.

Both the excavations and the division of the finds proceeded with the permission of the Ottoman Empire – including a subsequent legalization of the parts of the frieze that were sent to Berlin prior to the excavations. This is shown in detail by the records that were kept of the excavation campaigns of 1878–1886 and the division of the finds. These documents are known to German and Turkish experts and have been made available to a wider public in several exhibitions, including one at the Pergamonmuseum in 2011–12.