ForschungsFRAGEN: Pest Control

29.04.2022ForschungsFRAGEN: Pest Control

What is the worst pest in a museum? Is climate change affecting the insect situation in museums? What can be done in the way of prevention and how do you get rid of an infestation? Bill Landsberger, the insect expert at the Rathgen-Forschungslabor (Rathgen Research Laboratory), answers your questions about pest control in museums.

What is the worst pest in a museum?

Human beings? No, and in any case the term "pest" is purely anthropocentric. Nature knows parasites, parasitoids, predators, and decomposers, but not pests. These are highly specialized and adaptable organisms, with which we only come into conflict when, as part of the natural material cycle, they compete with us for resources that they need in order to grow and multiply – in this case, the objects that we keep in museum collections. It is nevertheless necessary to raise awareness and provide information for everyone in a museum so that people do not facilitate infestation by pests. After all, if you consider cause and effect, pests mostly get an opportunity as the result of our own careless behavior, for example if pests are brought in with objects for the collection or transportation packaging, and when windows or doors are simply left open for a while, especially in the summertime.

Out of a total of perhaps fewer than fifty significant cosmopolitan and synanthropic species [undomesticated species that live alongside humans ] that are found in museums, insects are the predominant cause of damage. In Central Europe, there are currently four main ones that endanger museum objects most often and which can potentially cause serious damage; the common clothes moth Tineola bisselliella, the varied carpet beetle Anthrenus verbasci, the bread (or drugstore) beetle Stegobium paniceum and the gray (or paper) silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudatum.

Is climate change affecting the insect situation in museums?

Global climate change has not yet had a serious impact on the occurrence of harmful insects here; remember that most museums, collection storage depots, and archives have a standard, air-conditioned climate. It's rather the case that people's idea of a comfortable indoor environment has changed over the last century, and that has had consequences. Fifty years ago, allowing for seasonal fluctuations, 17 °C and 65% relative humidity were the norm in museums, but nowadays 22 °C and 45% RH are more usual. Up until the middle of the twentieth century, the common furniture beetle Anobium punctatum was a widespread cause of damage in museums. In its place, the changed climatic conditions in museums, archives, and libraries now favor a deathwatch beetle species Nicobium castaneum and the aforementioned bread beetle S. paniceum, which are responsible for similar kinds of damage. A similar development has unfolded over the last few years with the gray silverfish C. longicaudatum, an invasive, non-native species that is spreading strongly in place of the silverfish Lepisma saccharinum, which has been common up to this point. The once-feared museum beetle Anthrenus museorum has disappeared almost entirely, but it has been replaced by potentially even more harmful species: the varied carpet beetle A. verbasci and the Australian carpet beetle Anthrenocerus australis.

What can be done in the way of prevention and how do you get rid of an infestation?

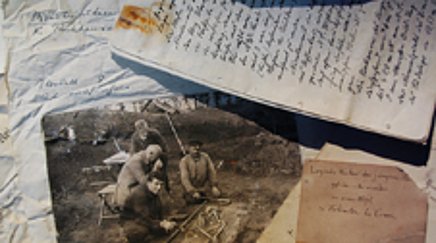

The SPK's integrated pest management (IPM) focuses on preventive measures and the intensive monitoring of objects in the collections. To prevent pests being brought in, all objects and materials containing organic matter must be thoroughly inspected and quarantined upon delivery. Since there is rarely enough time and space available for this, thermal or anoxic treatments are carried out as a precautionary measure. As an early warning system, our collections are equipped with pest monitoring devices in order to recognize the signs of an impending infestation, identify any ecological connections, and enable us to take countermeasures quickly. The regular examination of trap catches allows us to collect important data that reflect the momentary situation, that flag changes and any developing infestation in good time, and that record the success of countermeasures. By precisely identifying any pests that are present, we can respond efficiently with measures designed around the innate biological characteristics of the species concerned, so as to prevent similar occurrences better in the future. A thorough analysis of the causes is also crucial. This can mean checking the situation in a room and changing it to deter pests, closing gaps in the building envelope, creating physical barriers, correcting microclimatic deviations and, if an infestation is suspected, disinfecting individual objects by means of a freezing treatment or by keeping them in an oxygen-free atmosphere for a sufficient length of time.

Certain beneficial species, such as parasitic wasps and assassin bugs, are even used preventively against pests such as clothes moths, fur beetles, and bread beetles. And, trivial though it may seem, it is always important to check that the cleaners have done their work thoroughly. That's because even small balls of dust and fluff can provide pests with food, shelter, and – in the case of hygroscopic material – the moisture that they need to survive. For example, just a few cubic centimeters of textile fibers containing wool are enough to support a population of clothes moths that it would take an enormous effort to eliminate.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/e/csm_lupe_226_126px_057f2bcc80.jpg)